|

| Pech de l'Aze aurochs bone with deliberate markings. Lower Paleo (200,000 bp) (This drawing pilfered from Don's Maps) |

Art plays a huge part in our lives. Many of us dedicate our lives to creating, studying, or appreciating art. But did you know it was (and is) a crucial factor in the survival of our species?

|

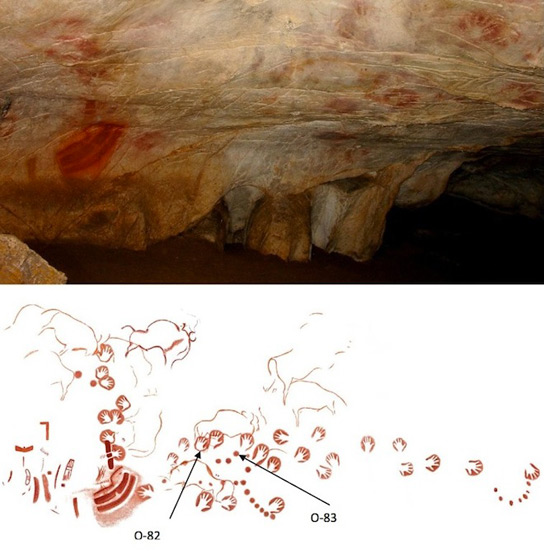

| Early Upper Paleo Designs in Ochre at El Castillo Cave in Spain, possibly made by Neanderthals! From the original article: "Some of the handprint outlines are at least 37,000 years old. Some of the red circles are 41,000 years old and could be several thousand years older. This is 10,000 years older than the paintings found in France, which were considered the oldest cave art." |

I have often wondered about the connection between art and evolution. In the Upper Paleolithic (around 50,000 through 10,000 bp), there is what many scholars call a "fluorescence" of culture, when art and technology exploded on the landscape. This is when we start to see amazing cave murals, vast leaps in tool-making and hunting techniques, and many other indications of a species (H. sapiens) that is becoming more and more complex. Art is the most startling and spectacular artifact of these changes, and has been a major focus of these discussions. It was believed that this was the very earliest art and that it was exclusively H. sapiens-produced. There have been innumerable academic discussions on possible catalysts for this renaissance. It seemed as if something drastic and sudden occurred that manifested in this renaissance. And it did correspond with the influx of H. sapiens into the regions in question. Was this the beginning of human capacity for abstract thought? language? stratified society? spirituality? Was this the advent of H. Sapiens dominance across the globe?

It has become apparent, though, that art was being produced prior to the Upper Paleolithic and prior to the advent of H. Sapiens, indicating that hominids were capable of abstract thought much earlier than originally believed. It's clear that art underwent an evolution of sorts, changing dramatically through time. It is also clear that there are physiological/neurological processes involved in the creation and perception of art. What does this mean? What does art reflect? What does it cause?

I believe that art is both a reflection of and a causal factor in the evolution of our species and our culture. Here's why:

- Art is a direct manifestation of our most primitive neural processes;

- Changes in art (techniques, styles, etc.) over time correspond with physiological changes in the brain;

- Art facilitates increased social cohesion in the following ways, and was therefore evolutionarily advantageous and selected for:

- Art facilitates (in addition to depicting or reflecting) spiritual/emotional experience and belief;

- Art facilitates and transmits political power.

PART I

Art as a Direct Manifestation of Primitive Neural Processes:

Cognitive Lines and the Visual Cortex

Any two-dimensional mark that we make on paper, stone, a textile, or in the sand may be thought of as the external representation of one of our most primal neurological functions: the ability of differentiate between objects in our line of vision and the space around them. The mark or line in our brain originates in the visual cortex (more precisely, the striate cortex) of the optic system, in the process that enables us to navigate through our world. An object that is within our view is separated from the space around it by what is perceived by the viewer as a line. Think of it as an outline. This permits the viewer to navigate between objects as she/he moves through space. These lines are crucial to an animal's survival. The brain responds to changes in these lines (which are infinite, happening with each movement of the viewer's body, each movement of the object that is being viewed, each change in the light, etc.) immediately, to which the viewer immediately responds (often subconsciously).With a greater insight, in recent years, of the functioning and structure of peripheral and central mechanisms of perception has come, likewise, a greater understanding of how the visual system has been forged by the exigencies of evolution (Gregory 1990). It has been suggested that over half the human cortex is involved in vision (Gregory 1990: 7-8) and the cortex, in toto, grew, initially, out of the need to process visual information (Gregory 1970: 12-13) — a case of form (graphic marks) following function (the neurophysical structure of the visual cortex). Consequently it is now possible, by graphic analysis of the Lower Palaeolithic (L. P.) and Middle Palaeolithic (M. P.) mark-making (and by implication later Upper Palaeolithic [U. P.] representational forms), to make a comparative analysis linking such artistic phases to the stages through which the early human visual system, shaped by the demands of survival, had already passed before the onset of mark-making, i.e. from a reactive to a more pro-active engagement with the immediate environment. (Hodgson 2000b)

How a Line is Analyzed In the Brain

The Striate Cortex

The striate cortex is known as the "gatekeeper," as most of the information going to the visual cortex is funneled through this area first. |

| Diagram from Webvision. |

The striate cortex represents an early stage in the brain's analysis of lines. The interpretation of lines by the modern human brain involves a hierarchy of simple, complex and hypercomplex cells by which the nature of information to do with line becomes more abstract. Different aspects of a painting are processed by different regions of the visual cortex (Livingstone 1988; Zeki 1993: 355), with the analysis of line in the striate cortex being of primary significance. Zeki (1993) has identified discrete cells in the visual cortex (V4) beyond the striate cortex as being responsible for the analysis of colour. Cells in the striate cortex are organised to respond to specific orientation of line and that perception may be fabricated from the accretion of selected features (Hubel and Wiesal 1979).

It is thought that the striate cortex is the origin of the phosphene/artistic primitive art form of representational mark-making beginning (arguably) in the Lower Paleolithic, which may be the precursor to later representational line drawings (the illustration below summarizes the appearance of phosphenes in prehistoric art; click on the picture for a bigger image). "Subsequent fully-fledged coloured paintings appeared in the Upper Paleolithic as a derivative of a separate, more recently evolved, but parallel, visual channel" (Hodgson 2000b).

|

| From Hodgson 2000b. |

The Magno and Parvo/interblob Systems

Livingstone and Hubel 1987 discuss separate but parallel processing of varieties of visual information.This can be divided into two broad categories, the Magno system and the Parvo/interblob system:

The magno system is the more primitive of the two systems, and is dedicated to enabling visual creatures to navigate in their environments, while the parvo-interblob system (higher developed in primates) adds the ability to scrutinize more closely the shape and surface properties of objects (Hodgson 2000, 9). “The perception of form would have been critical for survival and, over time, specifically selected for, which could explain why line components figured so prominently in early mark-making” (Hodgson 2000).

1. Magno System

- carries information about luminance contrast (light and dark);

- at level of primary visual cortex: analyses signals for depth, motion and global form perception

- decisions about which elements and discontinuities belong to individual objects, and thus is concerned with overall organisation of the visual world.

2. Parvo system

- information concerning colour, becoming more complex and elaborate in the primary visual cortex and higher-order centres of the visual cortex;

- Splits into the "blob" pathway for analysis of colour, and "interblob" pathway for high resolution of static form perception;

- Analyzes scene in greater detail.

COMING SOON!!!! I SWEAR!!!!

Hodgson, Derek. 2000a. Shamanism, Phosphenes, and Early Art: An Alternative Synthesis. Current Anthropology 41.

Hodgson, Derek. 2000b.Art, Perception and Information Processing: An Evolutionary Perspective. Rock Art Research Volume 17, Number 1, pp. 3-34.

MIRI

Interesting. To understand the initial steps in the process of human creativity is to really know who we are as a species, or at least perhaps how we tick, so to speak.

ReplyDeleteI think so!

Delete